A branch which is named after

Tsekh Otdelki

Opening of the exhibition on July 14 at 19:00

"Citizens!

Our window is open to a wonderful garden!

Dmitry Aleksanich"

Appeal No. 165 from the cycle "Appeals to Citizens",

artist and resident of the Konkovo district Dmitry Prigov (1940-2007).

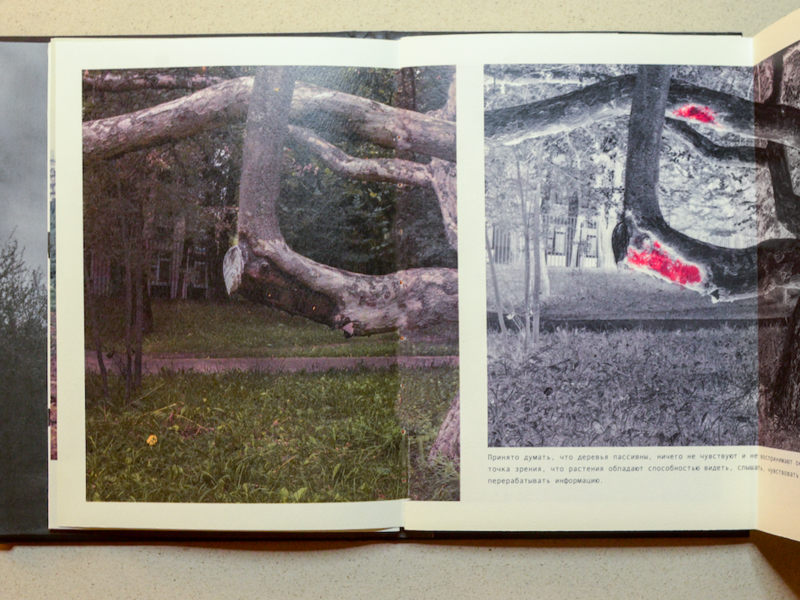

Fabrika presents the project of Alla Mirovskaya "A branch which is named after", dedicated to the problem of the relationship between man and nature, and in more detail – the relationship between people and trees and the attitude of people to trees. The exhibition project tells about an old apple orchard located in the South-West of Moscow. This is a project-museum, a testimony and memory of a place that the artist Alla Mirovskaya loves and knows since childhood. The exhibition will feature: an installation including photographs, texts, video art, an artist's book.

The author of the exhibition asks a serious question – do trees depend on man, or does man still depend on trees? Stefano Mancuso, an Italian biologist and author of How Plants Think, can answer this: “If plants disappear from the face of the Earth tomorrow, human life will last no more than a few weeks or months.”

In Moscow, as in other large cities of Russia that have experienced several waves of powerful urbanization over the past century, various green spaces have appeared within the city. These are the remains of forests, noble estates, private and state-owned orchards - the so-called "green belts" of the city, on which the quality of both air and life depends. These territories have different statuses, but a common pain: full of silent drama, the relationship between man and plants in the city. Reinforced by the consciousness of its superiority, the human will puts the existence of plants in the urban environment under a big question.

“I pass here twice a day and don’t see anything special in these trees,” Tanya says. Her daily journey to and from the subway passes through the garden. This makes it so familiar that the eye does not notice the bare, often hollow at the bottom of the trunks, dangerously tilted under their own weight. Apple trees are still very beautiful: knotty, tall, whimsically curved, strewn with wild fruits at the end of summer. But they are getting harder.

Every year old trees lose several important branches because they are cut down by the public utility. Dry large branches are considered emergency; it happens that their amputation is justified, but not always. However, no one wants to deal with this, because these are ordinary apple trees, by chance, wormed their way into the urban environment - they are not considered something valuable. Utilities cut the grass to the roots, destroying the fragile natural balance of the garden, “beautify” it by laying tiled paths along the roots of trees, depriving them of adequate nutrition and communication with their own kind (trees lead it with the help of roots), which is necessary for survival in an aggressive environment.

Residents of the district love the garden: they walk here all year round, in spring they enjoy the aroma of flowering trees, and have picnics on the grass. However, despite this, the garden disappears. The few local activists are powerless to change this, although they are desperately trying. Vera Makhankova, an artist and local resident, has been restoring old trees in the garden on her own for almost a decade. Contrary to her name, Vera does not really believe in the long-term success of this venture. But at the same time, he considers that if the saved tree stands for several years longer, then this is already a victory. Formally, public utilities help her, but in reality, help often turns into a profanation. Therefore, we can say that Vera is fighting almost alone for the life of apple trees.

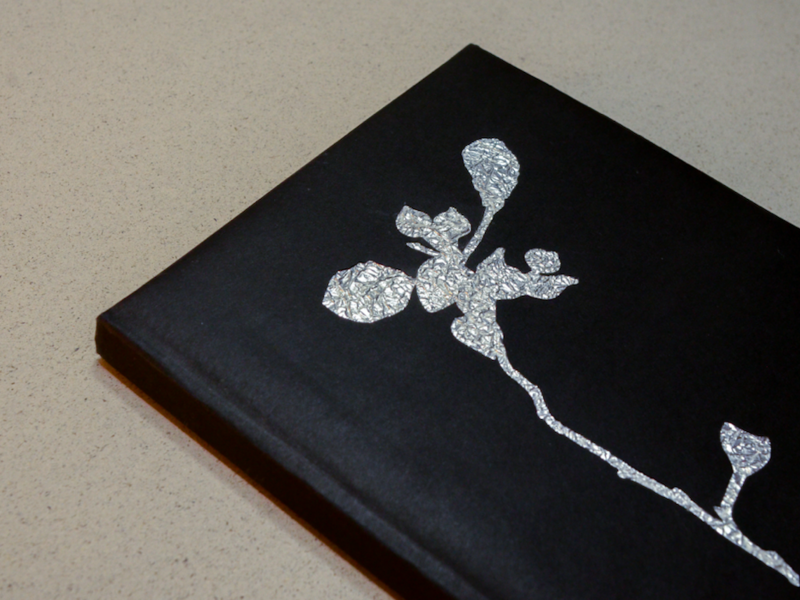

Artist Alla Mirovskaya about taking casts of apple tree trunks using foil:

“Household foil is a soft plastic material. The sheet fits snugly to the tree trunk, fixing its relief, bulges, bends, damage, the smallest tubercles and cracks. For accuracy, I pass my hand over the surface several times, smoothing and pressing. I shoot, marveling at how obediently a thin sheet of aluminum takes on a vegetative and even anthropomorphic form. Perhaps this is symbolic, or is it just me?

I remember the collection of ancient Roman death masks in the Pushkin Museum. These sculptural portraits of more than two thousand years ago convey the smallest details of the face and character of their character with amazing vividness. There is evidence that masks that are considered posthumous were made in the prime of life in order to capture the best in the appearance of a person and pass this on to posterity. A mixture of soft clay and warm wax was applied to the face, allowing the material to cure on the skin, and then the mask was cast in plaster or bronze.

I use foil because it is absolutely safe for the wood, it does not leave marks on it. But it is fragile, so I take photographs of the cast. Each cast is named. What is important here is the gesture of assigning the names of people – the inhabitants of the district to the inhabitants of the district – to apple trees, and that, albeit somewhat formal, effect of blurring the boundaries between the biological and the social that it carries with it.

In this way, I am trying to draw attention to the problem and "highlight" the important topic of the relationship between trees and people in a big city, where plants depend on people. However, the opposite is true. Stefano Mancuso, an Italian biologist and author of How Plants Think, writes: “If plants disappear from the face of the Earth tomorrow, human life will last no more than a few weeks or months.”

Alla Mirovskaya is a photographer, artist, curator and teacher, urban explorer, living and working in Moscow. In her projects, Alla Mirovskaya works with the themes of memory, place, and identity from a personal perspective. She studied at the Faculty of Journalism of the Moscow State Pedagogical University. Graduated from the Moscow Institute of Contemporary Art Problems (2015-2017). Participant of art exhibitions and projects in Russia, France, Italy, Denmark and the USA. Participant of photographic and photobook festivals in Moscow, Amsterdam, Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Zurich, Hong Kong, New York and Los Angeles. Author of ten self-published photobooks. Co-founder of the Russian Independent Self-Published group, a group of independent Russian photographers and artists who independently publish and promote photobooks both in Russia and abroad. Curator of the direction of art photography at the international festival "Photo parade in Uglich" in 2017 and 2019. Co-organizer of Fotobookmarket — a market for author's photobooks in Moscow and the Fotobookmarket Dummy Award book layout competition. Alla Mirovskaya's works are in the collections of the library of the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art (Moscow), NCCA-ROSIZO (Moscow), the Austrian Cultural Forum in Moscow, the Institute of Contemporary Art Chicago , the Phoenix Museum of Modern Art (USA), as well as in private collections in France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Great Britain, and the USA.

Alla Mirovskaya is a photographer, artist, curator and teacher, urban explorer, living and working in Moscow. In her projects, Alla Mirovskaya works with the themes of memory, place, and identity from a personal perspective. She studied at the Faculty of Journalism of the Moscow State Pedagogical University. Graduated from the Moscow Institute of Contemporary Art Problems (2015-2017). Participant of art exhibitions and projects in Russia, France, Italy, Denmark and the USA. Participant of photographic and photobook festivals in Moscow, Amsterdam, Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Zurich, Hong Kong, New York and Los Angeles. Author of ten self-published photobooks. Co-founder of the Russian Independent Self-Published group, a group of independent Russian photographers and artists who independently publish and promote photobooks both in Russia and abroad. Curator of the direction of art photography at the international festival "Photo parade in Uglich" in 2017 and 2019. Co-organizer of Fotobookmarket — a market for author's photobooks in Moscow and the Fotobookmarket Dummy Award book layout competition. Alla Mirovskaya's works are in the collections of the library of the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art (Moscow), NCCA-ROSIZO (Moscow), the Austrian Cultural Forum in Moscow, the Institute of Contemporary Art Chicago , the Phoenix Museum of Modern Art (USA), as well as in private collections in France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Great Britain, and the USA.